Genocide ain’t no Genocide?

Genocide. A word that triggers intense emotions. A word with some of the strongest connotations, comparable to rape, enslavement or torture. Genocide is the bad stuff, the one crime, especially horrendous, that has not been committed by any random country but by only a few. It immediately evokes associations with the Holocaust, killings in Rwanda or the killing fields in Cambodia.

Because of their extreme cruelty, and great number of deaths involved, these events are eternalized in history books and are dealt with in history classes at school. The term is highly politicised. Until today the Turkish state refuses to call the mass killings and deportation of roughly 1.5 million Armenians in the years between 1915 and 1918 genocide, because it does not want to belong to this club of countries that at one point in history descended into inhumane insaneness. This is especially true since it was not the Ottoman Empire but the Young Turks, the spark of the new Republic who was responsible for it.

Genocide is perceived worse than mass killings, war or forced relocation, and this might be because of the rareness of the event. Nowadays, unfortunately, media reports on mass killings, systematic kidnapping and enslavement of whole groups are present but rarely genocide is on the table. Right now, there are increasing demands to declare some actions committed by Daesh as genocide. This gives rise to several questions. Firstly, what exactly is the difference between genocide and for example mass killings and secondly, in what results this distinction?

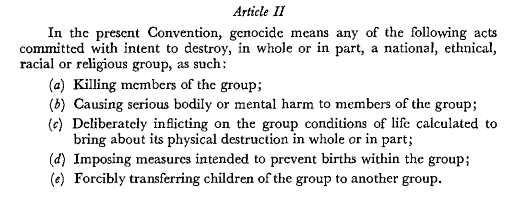

The term genocide became popular after Wold War 2, when the systematic and merciless extinction of six million Jews and the total capitulation of Nazi-Germany led to the establishment of the UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in 1948. In the convention genocide is defined as the following.

The article presents the crime genocide and introduces some conditions which have to be met in order that the crime is qualified as genocide. Three conditions are present. One set makes a selection of the nature of the victim group (national, ethnical, racial or religious) a second set makes a selection of actions ( (a) to (e) ) and a third and very important condition is the intent to destroy.

First, in juridical terms: In a trial, the defence of an accused of committing genocide can attack all three conditions, because all of them have to be met in order to convict the accused. The defence might have a hard time to deny the actions itself. Thousands of people were involved, and in many cases the world community paid attention. Equally difficult might be the denial of responsibility and intention, especially when the accused had a high position such as head of state, minister or even commander and there are reported speeches. The more successful strategy of the defence could be to attack another condition, namely the condition aiming at the nature of the victim group.

In practice this could mean, that the defence is not denying the killing of thousands of persons, and neither does it deny the responsibility of the accused. As long as the prosecution is unable to prove that the group intended to be destroyed is a national, ethical, racial or religious group, the conditions for the crime of genocide are not fulfilled. If the defence therefore is able to convince the judge that the group of victims is in fact a political group, the accused might leave the court as a free man.

It is a fundamental right of our understanding of justice that accused have to be convicted, based on a binding legal basis, which in that case would not be met. There might be other bases, such as ‘crimes against humanity’ or ‘the crime of aggression’ which present better prospect to trial the accused. So far, so bitter but fair.

But now, the political and common use of the term genocide comes into play. Imagine the outcry of felt injustice, fore and foremost by the victims of the happened events if the media announces “General X has not committed genocide”. It must sound like pure mockery. The problem is the socially constructed distinction people draw between ‘mass killing’ or ‘genocide’. In reality it makes no difference whether thousands of persons are killed because they were Muslims, Christians or Communists. But, based on the juridical definition of genocide, the distinction has found its way into the all-day language.

Moreover, the understanding of genocide that people might have, diverges greatly from its juridical definition. Based on the vagueness of the article, in juridical perspective, some situations not even including one single person killed could turn out to be genocide while others, involving thousands of deaths, are not.

What does that mean for the use of the term of genocide? Most importantly it is necessary not to be led by diffuse feelings and arbitrary associations, but rather to critically assess the reasons why the term genocide is used. Furthermore the problematic distinction should not lead to a relativisation of mass killings which were not defined as genocide. We do not forget the happenings in Rwanda or Cambodia but might not take into account others, which did not met the juridical definition. The single difference between them is a definition presented in an article, triggering certain clauses and effects. It has nothing to do with the actions itself and should not evoke comparisons about the cruelty or extent of the committed actions.

Featured Image:

Pixabay. “Genocide, History, Ground Memorial” Pexels. February 2016. Date Accessed: 19.02.2020. https://www.pexels.com/photo/genocide-ground-memorial-history-holocaust-276925/