Can politics still be poetic?

This article was inspired by a discussion organised by SIB Groningen, on the 12th March 2018, called “Poetry and Politics in Iran: The Power of Verse”. It was led by Professor Asghar Seyed-Gohrab an Associate Professor of Persian and Iranian Studies at Leiden University, who has specialised in Islamic spirituality and Persian mysticism.

The ideas of politics and poetry may seem as different as chalk and cheese, but actually many state leaders have also been poets, and poetry can be used as a mechanism to inform citizens about political matters. Politicians are normally depicted as using cool, clear, and collected language when communicating formally with citizens. If our politicians spoke to us in poetic riddles, with references to ancient literature, the message would be confusing, and it could be misinterpreted.

However, this is exactly how politicians in Iran choose to successfully inform their citizens. In Iran, Persian poetry has been at the heart of the political movement for centuries. In 1843, it was said, that in Iran’s history “lives have been sacrificed, or spared—cities have been annihilated, or ransomed—empires subverted, or restored—by the influence of poetry alone.” And in recent years, poetry has continued to play a vital role.

Recently, Iran’s president Rouhani used poetry when addressing the UN to address Trump’s claim that his government is a “corrupt dictatorship behind the false guise of a democracy.” Rouhani spoke of moderation using Persian literature from the 12th and 13th centuries. Some claimed his use of language essentially trolled Trump, who he accused of being all about “slogans” and not about “actions.”

Mohammad Javad Zarif Khonsari, Iran’s Foreign Minister uses twitter and other social media sources to inform the public of his concerns and hopes over Iran’s future and foreign policy. What may seem strange to Europeans is how, he does so using modern and ancient verses from Persian poets, and how ordinary citizens will reply with critic or support in the same manner. In Iran, even the illiterate are able to quote verse after verse of Persian poetry. Persian poetry has played an important role in Iranian politics in part because of its prominence in everyday life. When Javad Zarif refers to one line in a poem, the Iranian people are able to correctly identify where it came from and are able to further read into the situation.

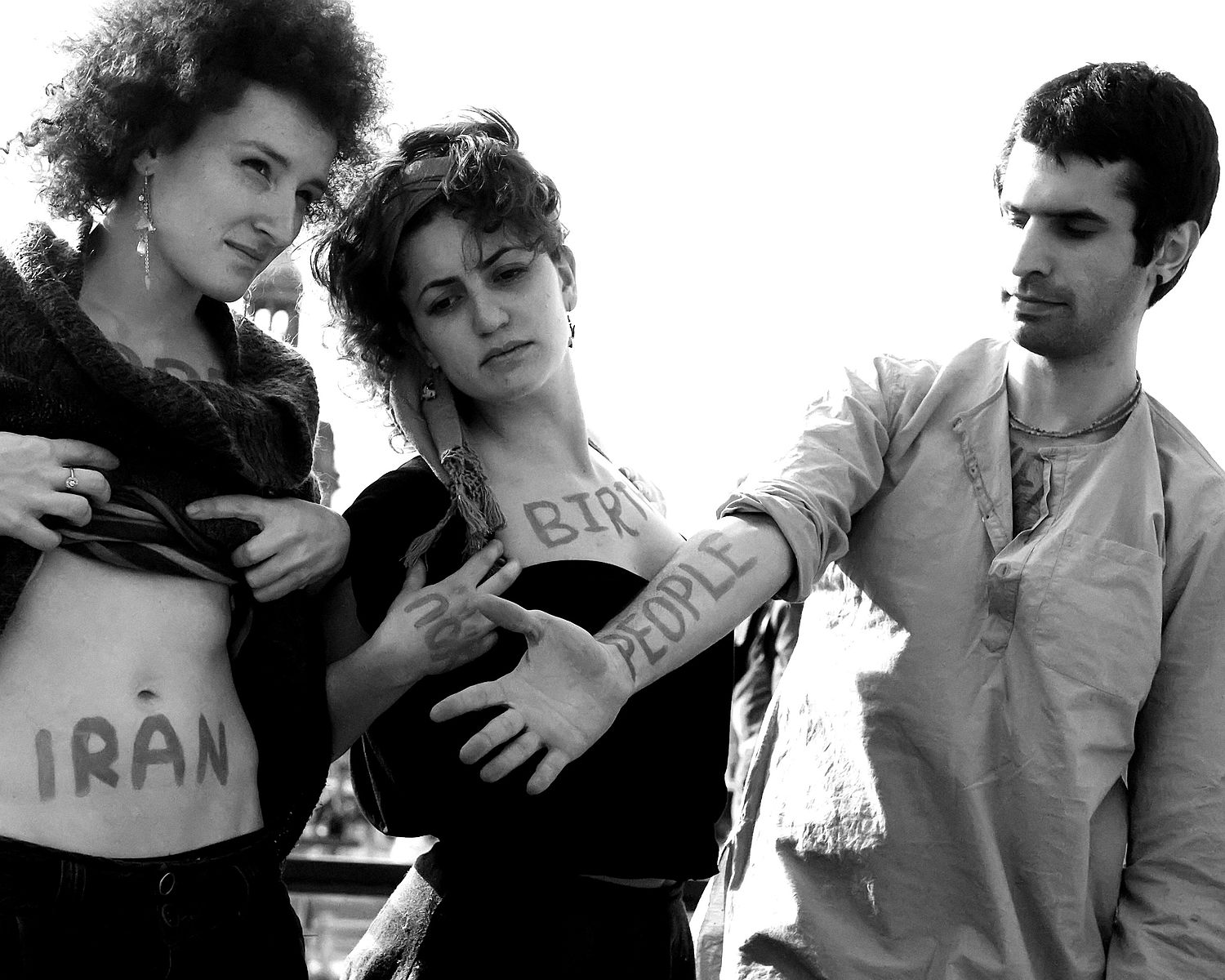

Iranian politics and poetry have historically been interlinked, and this was clearly seen in the 2009, Green Revolution. Where there were nationwide protests after the presidential election, which the protesters were convinced was rigged. The protesters demanded the removal of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad from office and many of them were arrested for their actions. During the protests people began reciting poetry from their rooftops and clips of this went viral at the time.

Nedā Āghā-Soltān a twenty-six-year-old, philosophy student, was shot during the revolution and the whole incident was captured on video and quickly spread throughout the internet. Many poems were written in her honour and they also became slogans for the revolution. Such as “Neda is not dead, the government is dead”. Her name means voice in Persian, and many called her the voice of Iran.

The use of poetry is fundamentally different when looking at Iran and Europe. It is difficult to find examples of European countries where poetry is as widely used and as important. In Iran poetry is a living tradition and is regularly used to reinforce political arguments. Poetry can help shape national identity, bring people together and still express a political situation.

How state officials choose to communicate with citizens, in order to bridge the gap between the governing powers and the people can give a unique insight into the country. With the increase in today’s technology many politicians choose to communicate daily through social media. Iran chooses to eloquently use ancient poetry to contact its citizens and explain the current political climate. A return to poetry may be what we need in a time where 280 characters measure our sonnets, and formality overrides the notion of emotive writing.

Featured Image:

Jos van Zetten from Amsterdam, the Netherlands (https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flickr_-_NewsPhoto!_-_Stil_protest_voor_vrijheid_in_Iran_(1).jpg), „Flickr – NewsPhoto! – Stil protest voor vrijheid in Iran (1)“, https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/legalcode

” In Iran, even the illiterate are able to quote verse after verse of Persian poetry.” !!!

as an Irish educator I simply couldn’t comprehend this.

well written and presented

Interesting idea. Anything that encourages blatantly undemocratic regimes to treat their citizens in a more democratic and humane way is to be welcomed.

I have to say, I’m not holding my breath……..